A little wander through the names in Swaledale

In writing the next of my Viking novels, I’ve had cause to spend time exploring the delights of Swaledale in the North Yorkshire Moors. Not that the area is unknown to me anyway, as I live not far from the dale, and have spent plenty of time there over the years. But when writing something historical based in the area, one is required to dig a little deeper than is perhaps the norm when visiting a place. I found myself trawling the place looking for the settings for scenes in the book. And perhaps that’s where I ought to start. I am carefully avoiding spoilers here, but in book 5, my Vikings visit northern England, as has always been the grand plan for the series, but in more recent years, this has been narrowed down simply by the realisation of just how Viking upper Swaledale is.

The lush Vale of York and the more gentle Wensleydale are a haven for Anglian and Saxon history, and there are remnants, both physically and in names, of those peoples in the lower reaches of Swaledale. Catterick, at the entrance to the dale, is derived from its Roman name of Cataractonium, and the nearby town of Richmond, the main settlement in the dale, owes its name to the Normans, though its predecessor on the site was the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Hindrelac. Similar names can be found in the lower dale, though it was the upper dale that caught my attention, and three names in particular drew me into setting my work there.

The first is Gunnerside, which has come down to us from the Norse ‘Gunnar’s sætr’, or the ‘pasture of Gunnar.’ The second is Arkengarthdale, and its settlement of Arkle Town, which derives from the Viking name ‘Arkil.’ The third is Ravenseat, for ‘Raven’ comes from the Norse ‘Hrafn’, which of course means raven. Such a profusion of Norse names meant I simply had to use this for my setting. But over recent trips and in conversation with friends who live in the dale, I have found myself investigating the story behind many names in the area, and below, I’m simply going to list a few for your entertainment and edification.

* * *

Blea Barf – Blea coming from the Old English for ‘happy’, and barf referencing hills through the Norse ‘berg’ from which is is derived, then Blea Barf should truly be a ‘happy hill’

Bloody Vale – Though there’s no confirmation of how this or the Bloody Wall got their names, it was likely one of the various wars that roved across the Pennines over the past millennium or more. Or possibly a farmer kept tripping over and getting irritated.

Crackpot – From Kraka, again Norse, Crackpot actually means Crow Pit, a reference, probably to the cave just up the slope.

Jingle Pot Gill – With no confirmed explanation, I can only put the name here down to the fact that the area contains some of the highest concentration of lead mining remnants in Swaledale. I’m sure a pot of lead would jingle, after all.

Muker – Nothing at all to do with a head cold, Muker once again comes from Norse origins, from the name Mjor Aker, meaning a narrow field.

Scabba Wath Bridge – Scabba Wath is one of the most fascinating names to be found in the dale. Wath being derived from the Norse for a ford, one might think it a Norse name, referring to the ancient ford just downstream of the bridge. However, the best guess is that Scabba comes from skalba, which is a Celtic word for a gap or cleft, meaning that Scabba Wath Bridge is three words, each probably from a different language. It may be that the Norse Vikings coming to Swaledale from Ireland via Cumbria brought with them the odd Celtic word, and this might still therefore be a Viking name. (Side note, for further multiple name fun, see Torpenhow Hill in the Lake District!)

Scurvy Scar – My only guess here, unless people didn’t eat enough fruit, is that the area is named for the Pyrenean Scurvygrass that grows in damp areas of the Dales, often where metal working has taken place, both of while apply to Scurvy Scar.

Skeb Skeugh – Thoroughly Norse, this comes from Skogr Skeifr, meaning something like ‘Crooked Woodland.’

Surrender Bridge – The only thing we can probably say about this amazing little bridge between two lead smelting sites is that it probably has nothing to do with a conflict. It may take its name from the Old English ‘sur’, meaning sour or damp. Don’t know about you, but I shall go on imagining it to be the site of an ancient battle.

And of course, I have to leave you with……

Wham Bottom – This bottom is on top, up on the hills above Gunnerside, but that is because ‘Botn’ is old Norse for the head of a valley while ‘Hvammr’ is Norse for a grassy hillside. So forget playful spanking. Wham Bottom is a grassy slope at the head of a valley, which pretty much describes the site.

TROOPER JANE: A CIVIL WAR TALE

“This, dear lady, is what my father would have referred to as an ‘uncomfortable situation’.”

“The chair is not giving enough for your ignoble behind?” Jane replied with every ounce of pluck she could muster. They’d been here only half an hour and already her arm was aching.

“You continue to astound me, Lady Jane. There are masters of horse and Lords in Parliament who would quail at even the thought of speaking to me in such a manner.”

“Perhaps they would feel different with their tenants strewn across the landscape feeding the crows, their home invaded and half their enemy encamped on their lawn.”

Oliver Cromwell, Lieutenant General of Manchester’s horse and scourge of the Royalist cause merely smiled a strangely lop-sided smile that seemed genuine on his blemished, plain and yet somehow entrancing features.

“In fairness, Lady Jane, this could all have been very easily avoided. I seek your brother and redress for his part in the stand against parliament. I am not in the business of threatening women or reducing grand houses without cause. Surrender Sir William to me and I will leave you in peace to deal with what remains of your household and tenants. My army will move on without a shot fired.”

Lady Jane Ingilby felt her hands drooping under the weight of the pistol and forced herself to raise it once more so that it aimed for that inscrutable face.

“Your intentions are betrayed, master Cromwell. I saw from the window the executions of the prisoners against the church wall. I witnessed your particular idea of redress.”

“Your brother led his cavalry with that gilded fop Prince Rupert.”

“So did many gentlemen of value, others of whom escaped the field. Why victimise the lord of Ripley in such a manner.”

In response, the most powerful military leader in the north of England simply smiled as he reached up. Lady Jane gestured threateningly with her pistol.

“Permit me, Lady Jane.” Ignoring the threat, Cromwell unfastened the stiff collar of his coat and pulled it aside, lifting away the lace collar beneath to display a bandage that had been wound around his neck long ago enough that a blossoming red rose showed through at the side.

“A dangerous place to be wounded, Master Cromwell. You are lucky to still have your head.”

The puritan’s smile altered somehow, barely perceptibly, but leaving an expression of ‘humour’ that managed to convey neither mirth nor warmth.

“I do not believe in luck, my lady. I owe my continued presence on this mortal coil to your good brother’s lack of practice with his carbine. Despite the shock and the sudden blinding pain, I managed to maintain a hold on my wits and before I turned to seek the assistance of a doctor, I looked across at the lunatics who had charged us under Byron’s orders and there he was, armoured from head to foot like a grand old knight of the realm, that somewhat distinctive white star banner fluttering overhead, still holding that carbine aimed at my head, the barrel smoking.”

Lady Jane paled visibly in the light of the fire, her hands gripping the pistol shaking slightly before she realised and steadied herself.

“Are you sure it was he. Things get… must get somewhat confused in the heat of battle.”

“It was Lord Ingibly. And in the aftermath of what must to your cause be the most utter and humiliating defeat, I am inclined to be merciful to prisoners wherever possible, but I must make an example of a man who very nearly sent me to my God.”

Lady Jane recovered a little of her colour.

“What, then, makes you certain that I will not simply shoot you tonight and finish the job for him?”

Cromwell smiled and sat back in the chair.

“I hope you will not think it unacceptable if I leave my collar open? Your fire warms the room so thoroughly and I am over-attired for such an environment.”

Barely pausing for her nod of assent, he pursed his lips. “I do not believe you will shoot me. You are known to be a lady of honour and a gentle creature, and I find it hard to picture you having the mettle to carry out such an act in cold blood…”

“I may yet surprise you, Master Cromwell.”

“Secondly, there is a validity to my accusation and you know that, despite my need for justice I will not simply have your brother executed. He will stand trial as a man of his lineage should and, given the number of my peers who are not my most strident supporters, there is every likelihood that he will walk away with a minor punishment.”

That empty smile came back as he leaned forward again.

“And, of course, there are hundreds of cavalry, pikemen, musketmen and even cannon outside your gatehouse awaiting me. The consequences of causing me harm are unthinkable, I’m sure you will agree.”

”Then we are at an impasse, Master Cromwell. I invited you in under the offer of truce to discuss the matter. If William were here, which I can assure you he is not, then you must know that I would never let you take him. And yet I cannot hope to overwhelm your force.”

Cromwell scratched his cheek. “It would appear that way. Perhaps I could beg your hospitality and pour myself a glass of this excellent-looking claret while we talk?”

* * *

The church clock struck three and Lady Jane awoke with a start. Her heart pounded as she panicked and realised the danger she had been in. Her hands came up sharply with the pistol held firm as she blinked at where Cromwell should have been sitting. How long had she been asleep? Idiot. She was tired, and for damn good reason, but tonight of all nights she needed to be alert.

Her eyes strayed around the room desperately and she felt a wave of relief wash over her as they fell upon Oliver Cromwell, standing by the fire, the same – apparently untouched – glass of claret in his hand as he perused the bookshelf next to the ornate fireplace.

“I… you?”

“Fear not, Lady Jane. Fear not. You have a remarkable collection of the classics here. A very educated family, then. I had heard that. In similar rooms in other great houses I have come across hidden chambers and crannies for the hiding of papist priests. I do somewhat hope your brother is not spending the night in just such a place while I experience the comfort of his favourite chair and his best claret?”

Lady Jane felt the catch in her throat at the memory of William’s return. She had only been in the house for five minutes herself, wiping away the mess and perfuming herself, when her brother had rushed in, removing his armour and helm and blathering about Parliamentarian pursuit. Without waiting to discuss the situation, he had barrelled up the stairs and to the tower, where he had pushed and shoved his way into the very priest hole of which Cromwell now spoke. Fortunately it was not in this room and was far from Cromwell’s grasping fingers.

“That is the armour” he said, suddenly, gesturing with a lazy finger to a suit of cuirassier armour standing in the corner of the room. Again, Lady Jane’s heart skipped a beat.

“I beg your pardon?”

“This is the armour. You brother’s armour; somewhat unusual and outdated. So few cuirassier regiments these days, though I note this armour goes back some way beyond our current unfortunate conflict.”

“I fear you are mistaken Master Cromwell. This armour is merely decorative. It has stood in this room as a testament to our family’s valour for many years.”

Cromwell gave her a knowing smile and strode across the room to the armour.

“I have to disagree, Lady. I took the opportunity to examine it while you slept. It is clean and recently oiled.”

“We like to keep our ornaments in good condition.”

“It also smells of fresh leather, of horses, of gunpowder; of battle. But most telling is the number of fresh scrapes from blades and two dents from musket fire. All new. This is definitely the armour. And that means my would-be killer is definitely in this house.”

“Because my brother removed his armour here is no good reason to suspect that he remains in the building.”

“Perhaps not; and yet I remain convinced. Perhaps we could visit your kitchens and see what your servants have in the way of cold meat and bread. I have to admit to a keen hunger following my day’s exertions.”

The commander took a few purposeful steps towards the door and Lady Jane rose from her seat to intercept, the pistol tracking his movement, though her leg almost gave way as she turned awkwardly and had to right herself.

“I do hope, dear lady, that you are not harmed in some way?”

“An old weakness in the knee, master Cromwell. Nothing more.”

The general of horse smiled and stepped back two paces to the armour, running his finger along two of the dents, one of which ran front to back across the outside leg just above the knee.

“It must have been extraordinarily tense abiding here while your brother and all your tenants fought for their misguided loyalties on that bloody field. You must have felt the angel of death breathing in your ear all afternoon. Too often soldiers do not spare enough thought for those we leave at home.”

“I was not at home, Master Cromwell.”

“No?”

“No. I spent the evening in prayer for all our souls in the village church.”

“I have no doubt there will be many people to corroborate that. I must say that you look strangely comfortable with a pistol in your hand, good lady. I have rarely found a lady of breeding who knew how to hold such a weapon for war. Indeed, many would have been quite incapable of loading such a gun. And yet I have the distinct impression that, should I give you cause, you would put a bullet in me with neither hesitation nor difficulty.”

“You fail to notice the shuddering in my hands, Master Cromwell. I am no warrior, though my heart is strong and I will not baulk at the thought of taking a life if it should protect my brother.”

Again, Cromwell smiled with a knowing and infuriating look. “The strongest soldiers will shake from holding aloft a pistol for so long without pause. I note with interest, though, that the barrel is trained upon my head unerringly. You have a singular talent unusual in your breed.”

Lady Jane nodded. “Then mayhap you would be more comfortable returning to your force outside my door?”

“Come now, Lady Jane. Let us dissemble no more. It becomes clear to me what transpires here. I am intrigued to know whether your brother was even aware of your presence in the field? I suspect not. And yet you fought in full armour under his banner. And moreover at the front of the army, joining that ridiculous and ill-fated charge against my wing.”

“I?”

“Please do not insult my intelligence, Lady Jane. I have met your brother. He is a tall and well built fellow. It would be near impossible for him to don this armour, which was made for a smaller man. The sword wound to your leg? You should have your knee looked at by a doctor. Even if blood is not drawn, damage can be done to the bone.”

“Then if this is what you believe, Master Cromwell, clearly it is I that you need to take outside for trial, and not my brother. Perhaps we can come to an arrangement? If I leave with you in the morning you could forget all about William?”

The great general paused and frowned for a moment as if considering her proposal, and gave a single, deep belly laugh.

“It is a tempting thought. Not because I would wish you harm, but just to see the looks on the faces of my officers. Can you picture them? No, Lady, I cannot agree to that. I would be the laughing stock of the army if I brought a woman assassin out for trial. I would be a laughing stock if it were known that Sir William’s sister was the faceless knight at Marston field who almost took my life.”

“So another impasse is reached, Master Cromwell.”

“Hardly.” Finally, her ‘guest’ took a sip of the wine he had been coddling for many hours. “I try not to indulge too much in wine. It ill-befits a man of pious ways and can addle the wits at unhelpful times, but I do have to admit to an occasional desire for a good claret. A good claret is rich, full bodied, shows strength and taste, with subtlety and refinement. A good claret can ruin one’s gut and addle one’s brain and yet leave one feeling grateful for the opportunity.”

He finished the drink and replaced the glass on the table.

“You, Lady Jane Ingilby, are a good claret.”

Striding to the window and ignoring the pistol muzzle that followed his every move, he flung open the leaded glass and leaned out, peering past the gatehouse to the army gathered in the street and the field beyond.

“Tomorrow morning, dear lady, we march for York. I will endure the complaints of my peers for having tarried here and still failing to capture Sir William, who clearly fled Ripley when he heard that I approached.”

“You are leaving, Master Cromwell?”

The parliamentarian commander smiled and fastened his collar. “If you are content to play hostess until dawn, I will tarry just that little longer. I do not relish returning to my flea-bitten bed in the inn before light. But then, yes, I will be leaving.”

“And my brother?”

“The King’s cause is now lost, Lady Jane. Advise your brother to lay down his arms for good and never to cross swords with me and all will be fine.”

“And that’s it, Master Cromwell?”

“As I said, Lady Jane, I am sparing with my drink, but I do have a fondness for a good claret…”

Son of Mercia by M J Porter

I am primarily an author and reader of Roman fiction. I occasionally stray from that, but I have always claimed a general lack of interest in Dark Age England. Indeed, when Canelo persuaded me to write something of that era, my stipulation was that is was far removed from the usual Dark Age NW Europe, and I ended up writing in the Caucasus and the Byzantine world, which is more in my sphere. So where does this leave me with the Dark Ages in England? Well, I am extremely choosy. I am no great lover of Cornwell’s Dark Age books (while I love his Sharpe series), and various other similar series have left me cold. I have enjoyed Giles Kristian and Robert Low’s Viking adventures, but of England, until recently the only books that truly grabbed me were James Wilde’s Hereward series, and Matthew Harffy’s Beobrand books. That being said, M J Porter is an author who has been on my radar for a while, thanks to a number of mutual friends, and when I discovered her new novel on Netgalley, I was inclined to give it a try.

The blurb:

Tamworth, Mercia AD825.

The once-mighty kingdom of Mercia is in perilous danger.

Their King, Beornwulf lies dead and years of bitter in-fighting between the nobles, and cross border wars have left Mercia exposed to her enemies.

King Ecgberht of Wessex senses now is the time for his warriors to strike and exact his long-awaited bloody revenge on Mercia.

King Wiglaf, has claimed his right to rule Mercia, but can he unite a disparate Kingdom against the might of Wessex who are braying for blood and land?

Can King Wiglaf keep the dragons at bay or is Mercia doomed to disappear beneath the wings of the Wessex wyvern?

Can anyone save Mercia from destruction?

Review:

I did not read this blurb before I began. In fact, I went into the book completely blind, other than loving the cover. They say never judge a book by its cover, but to some extent we all do it. This one is lovely.

I will get my niggly negative out of the way immediately, as it is a matter of personal choice and may well not affect other readers. Simply: I do not find the first person present tense easy to read. I am comfortable reading in first or third person, but usually in past tense. That being said, Son of Mercia is well enough written that after a while I found myself not only accepting the tense, but actually appreciating some of the immediacy it lends the story.

Son of Mercia takes place entirely in what is now the English midlands region (ancient Mercia, surprise, surprise), centering largely on the capital of Tamworth but with cameos of other places including Offa’s Dyke. Much of the action, however, takes place in the wilderness. Recorded knowledge of Ninth Century England is sparse enough that much of what we need to picture of the world of the novel is born from our imagination, nudged in directions by the skilled author. The milieu Porter builds is vivid and realistic, familiar and deep, the detail teased from our own imagination by the writing.

The history on which the story is based is recorded in chronicles, as we learn in the author’s note, but, just like the Roman texts I use, these chronicles are subject to spin and bias, and so in order to build a realistic view of the world in which the tale is set, sometimes it is necessary to bridge gaps in logic. Porter is fortunate, perhaps, in having chosen a character and a series of events that directly affect this history, while largely taking place in the unrecorded periphery. This allows her to narrate great events while telling a much more personal story, the two becoming closer and closer aligned as the tale goes on.

What of the characters, then? The principle character is a young man named Icel, related to a renowned warrior, but himself tied to a well known healer as her apprentice. As political and military disasters unfold, and Mercia stands on the brink of oblivion, facing rule by the King of Wessex, Icel’s uncle, one of the king’s warriors, decides the time has come to flee this foreign control, He takes Icel and another young warrior and rides away, seeking somewhere to stay out the way. But over the many months hiding, events gradually conspire to pull them back to the world.

What really grabs me, character-wise, in this book, is Icel’s character. In Dark Age/Early Medieval novels there is a propensity to make every major character a warrior, hard as nails and invincible. Icel is not one of these stereotypes. He is a passive, pacifistic, nervous, quiet academic sort, low born and unimportant. As such he is a true breath of fresh air as a protagonist. Indeed, the freshness of this is not confined to Icel. His companion, the young would-be warrior is a frustrated, untrained lad, and even the uncle, who is clearly a great warrior, seems to spend much of the book undergoing repeated treatment for horrible wounds. He is a great warrior. He fights, he kills and he survives, but he does not walk through it all untouched. He suffers through it.

Another aspect I enjoyed is the small detail. This is evident in much descriptive of locales, of structures and of the landscape and nature, but nowhere is it more evident than in the treatment of medicine and surgery. I am used to Rome, which is a strange mix of magic/folk cures and actual true medicine. The Dark Age healing Icel and his teacher display here are a mix of herbalism and folk cures, but there is less true medical and surgical knowledge now, and time and again a wound is completed with searing closed and hoping. That being said, the knowledge of herbs, poultices and natural cures and their application is excellent, and gives the book all the more depth and colour.

In short, Son of Mercia is a profoundly personal book, centering on believable and sympathetic characters, telling us of momentous events in 9th century Britain through the eyes of the nobodies on the periphery. The story at times seems more an introspective personal journey for Icel than any kind of saga, but as the tale progresses, and politics drag our characters back into the crucible, war is inevitable. The battle scenes are as as deep and personal as the rest of the book, and no lover of Dark Age warfare is going to be disappointed.

Son of Mercia is personal, real, fascinating and satisfying. It is out on Wednesday 16th, but you can preorder your copy now.

Hadrian’s Wall: Day 1

The challenge: For the Turney family, kids and dog included, to walk the length of Hadrian’s Wall in small stages over the course of 2022. It will be done in such bite-sized chunks for a number of reasons, including little legs, fat dads and a pathological need to document anything Roman that comes into view. So we began today. Following a brief stop at Beckfoot fort (Bibra), which was part of the western sea defences extension of Hadrian’s Wall, we dropped the car at Drumburgh, the second fort along the wall from the west, and then took the bus to Bowness on Solway, the western terminus of Hadrian’s Wall. Nothing remains to be seen of Bowness (Maia) fort, but there are tantalising glimpses in the village. This is where our journey began, and what follows in the form of photographic evidence took place over a couple of hours and includes more than just Roman goodies,

Jack Lark is back… with a vengeance

I have been suffering a reading ennui for a few years, and have restricted what reading time I have to my main subject and era: Imperial Rome. It was a simple time thing. I had no time to read, and no inclination really, given that I was editing and reading my own work over and over again.

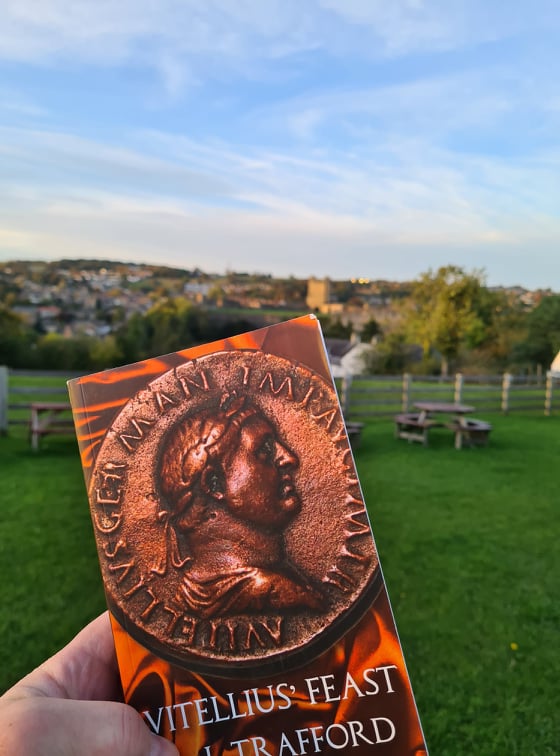

Then, this summer, I made the decision that I needed to drop work for times and actually rediscover reading. I started with a make-or-break foray into a new author: L J Trafford. It worked. Her books enthused me and rekindled my love of historical fiction. I read all four volumes of her excellent series in a row. Then there was that horrible moment. If you’re a reader, you’ve come across it. You finish a breath-taking series, and there is almost no chance that the next book you read will come close.

This is when it helps to have a set number of authors on your list who are so damn good that they could write a shopping list and you’d finish it and be waiting breathlessly for volume 2. There are only a few writers that guarantee me that, and most of my go-tos I am up to date with. I was incredibly lucky therefore to discover that Paul Fraser Collard’s latest Jack Lark book was now out.

I started reading Paul’s books back when he released his first novel, The Scarlet Thief, eight years ago. Scarlet Thief introduced us to Jack Lark, a character who, despite unexpected depths, fits into the traditional and comfortable mould of the ‘loveable rogue’. Jack steals the uniform of British officer heading out to service and assumes his identity, leaving behind a crappy life of poverty in London’s East End. His deception takes him to the Crimea and to the battle of the Alma, one of history’s less famous, but more bloody, battles. But Jack’s ruse cannot last, and when the first book finished, I could not understand how Paul could write a sequel.

But write a sequel he did. I read it voraciously. And astoundingly, he managed to keep Jack moving as a principle character, and even advance him. I was hooked. I read every Jack Lark as it was released. He moved through India and Persia, Italy, then across to America in time for the civil war and beyond. Then, as I mentioned earlier, I lost all my free reading time, and stopped following fiction for 2 years.

I picked up Commander. As it happened, although I’d missed the book in between this and the last one I read, my OCD collector thing meant that I had bought Fugitive anyway. The time had come.I read Fugitive, having finished Trafford’s series, and was immediately straight back into the Jack Lark world, loving every minute as he struggled across Abyssinia. I ran straight on with Commander. The odd thing is that though Jack has changed over a decade of books, and can be quite dark at times, even in his bleakest moments, the reader connects to him, because that ‘loveable rogue’ from book 1 has never been vanquished.

Commander takes Jack from Egypt in the British colonialist’s dream of opening up the heart of Africa to British trade and governance. It is an adventure fair and square. Taking an unexpected offer of employment from a true British adventurer, Jack is given the mandate to form a small elite corps from Sudanese and Egyptian troops to help the enigmatic ‘Sir Sam’ take a massive convoy and army upriver from Khartoum. He meets a fascinating French ivory trader with whom his destiny is entwined, and so begins an expedition into the wilderness. The sheers scale of the British plan is stunning, and I wondered how Paul was going to cover it in any less than three books, but the story that unfolds is pacy, exotic and thoroughly satisfying.

Part of the great value of this book is the feel and atmosphere it evokes. From early on, it gave me the urge to watch the movie The Ghost and The Darkness again. It is deeply evocative of the untamed wilderness of Sudan and central Africa. There is hardly a moment or a scene in it that fails to translate from the page to the mind’s eye with instant smoothness. It is almost cinematic in its atmosphere.

But there is more. Commander is at least as much an exploration of the psyche of the soldier, the mercenary, the colonialist and the killer as it is an adventure. Jack is a damaged man. Sometimes he realises it and makes and effort to deal with it. Sometimes he blindly accepts it, and plays the role nature seems to have dealt him. This book presents him with an ethical dilemma, and is a struggle for Jack to accept himself. He is a taciturn man, a straight talker, but the one person he repeatedly seems to dissemble with is himself. In the heart of Africa, though, with a small corps of soldiers, in the midst of ivory and slave trading and wicked, wicked men, he will find his soul laid bare.

He will find redemption.

If you have read the other Jack Lark books, be assured that this tenth volume is every bit as good as the first and is a tour de force. If you have read none of them, hunt down the Scarlet Thief and start your journey. You’ll not be disappointed.

The Four Emperors

Once in a blue moon, you come across a book, or series of books, that’s a game-changer. At the height of my reading, a few years ago, I was reading a novel a week. As time wore on, my writing commitments became heavier and heavier, and I was spending so much time looking at my own written words that, when it came to downing tools, the last thing I wanted to do to relax was look at more words, and so my reading dwindled, and dwindled to the point where I was not reading fiction at all. Oh, I was still reading tons, but it was all non-fiction research material for my own work. I hit reading rock-bottom, I guess.

Cue this summer. The family take a holiday every year to Wales and every year I do a little work while I’m there, because I’m so permanently busy. This year, I said ‘No.’ I would not work while we were away. I was going to actually relax. With a sort of half-hearted hope that I might rekindle something, I looked along my (extremely well-stocked) book shelves, searching for something that would whisk me away and drag me back into a love of reading. Of all the authors on there, my eyes fell on the copy of Palatine by L. J. Trafford.

For transparency, Linda Trafford has become a friend over the years. We both write Roman fiction and we both attend the Eboracum festival each summer, laughing and conversing over our book stalls. Years ago, while I was at Eboracum, I had bought her books and got my own signed copies, but then my reading ennui hit, and I never actually got round to reading them. They sat on the shelf in my office. Until this August. Palatine came with me to Wales. I began reading it the first day, and I was hooked by page 2. Totally unexpected for me. I write Rome, I research Rome, I travel Rome, and so to some extent the last thing I want is to indulge in more Rome. Yet the book dragged me in. By the time the hol was over, I had finished Palatine and was twitching to get to book 2. Since then, It’s been 2 months and I’ve read all four of L. J. Trafford’s Four Emperors series. That’s roughly a book a fortnight, something I’ve not done in years. I am now nervously trying to decide what to read next, as little could positively follow up on the series. So why is it so good? What’s it about?

In a nutshell, the series covers the infamous year of the four emperors (68-69 AD) from the time of Nero’s decadent last days, through the usurpers, wannabes, lunatics and generals who scrambled for power when the emperor died, right until the Flavian family settled on the throne and Vespasian brought things back to order. That’s the potted history. I’ve always been a little hazy on that year. I know the basics, but it’s a period I’ve avidly avoided thus far due to the sheer complexity. Too much happens too fast to untangle and portray, or so I thought. Perhaps I shouldn’t give you spoilers, but really this is old news for anyone interested in Rome, so here’s the potted version. Nero becomes too corrupt for some of his court. He is overthrown by the governor of Lusitania, Galba, and commits suicide. Galba arrives in Rome but quickly discovers that he’s completely mis-calculated what he needs to do, pissed everyone off, and ends up being deposed. The man who replaces him is Nero’s old friend, the notorious playboy Otho, but even before Galba’s body is cold, in Germany, the governor, Vitellius, is proclaimed emperor. Thus starts a small but utterly brutal war. Otho joins his predecessors, leaving Vitellius on the throne, but the big fat bastard can’t get comfortable, because the governor of Judea, Vespasian, has now been proclaimed emperor by his troops. Cue a secomd war, which rages right in the heart of Rome, and which finally leaves Vespasian in charge with no opposition, and the civil war is over. That’s the potted history. Very bullet point. There’s clearly a lot more to it than that.

There are four books in the series. Palatine tells the tale of Nero’s final days and the rise of Galba. Galba’s Men (not surprisingly) tells of the brief but very eventful reign of Galba and the plot of Otho to replace him. Otho’s Regret gives us the reign of the playboy emperor and the rise of the Vitellians in Germany. And finally, Vitellius’ Feast tells us of that emperor’s appalling reign and his demise along with the rise of the Flavian family. Very neat. But, I hear you ask, who is the protagonist in this tale? I mean, with five different emperors involved, who could possibly tell the whole story right the way through them all? That, of course, would have been my stumbling block. And that’s because I would have been looking among the great and the good for someone who could have witnessed it all. Linda Trafford, on the other hand, went an entirely different way, with stunning results.

Trafford’s cast of principle characters are uniformly slaves and freedmen of the palace. The fact that the first book is called Palatine makes immediate sense now. Her characters are a mix of historically attested people and fictional narrators, and the genius of her work makes it hard to tell what is given history and what is her own creation. There are other characters who come and go, such as emperors, praetorians and their commanders, young noblemen etc, but the main cast consists of the historically attested Epaphroditus, Nero’s secretary, who runs through the series, and more importantly and the prime point of view of the books, his own secretary, Philo, a freedman plucked from Trafford’s imagination. Then there is a flouncy catamite, an ambitious messenger, a self-obsessed announcer, a brutal slave overseer, the empress’s towel girl, and an ordinary family living on the Viminal hill who become more and more tied up in events as they proceed. The genius of this, which had never occurred to me, is that slaves and functionaries are ignored largely, by the great and the good. They witness everything, while rarely being part of it. As narrators it was a visionary stroke to choose these characters to tell the tale.

But why are they so good? Well that is born of several factors. The first, for me, is the humour. I find that in historical fiction, and particularly in Rome, there is a great tendency to be over serious. So many Roman books are all doom and gloom. That was what had made me love Ruth Downie’s Medicus novels. They had a gentle, human humour that was a breath of fresh air in the genre. So too Trafford’s characters. Oh don’t get me wrong. She does not shy from portraying brutality and wickedness. But despite that the books are filled with that same gentle, real humour that makes them so much more readable.

Secondly, there is the setting. Since writing these books, Trafford has gone on to move into non-fiction, with books on How to Survive in Ancient Rome, and Sex and Sexuality in Ancient Rome. Simply following her on Facebook will give you an idea of just how knowledgeable she is on the era. And that shows through in the books. They are humorous, exiting, and pacy, and yet consistently inflected with real colour and history. Every aspect, from toilet habits and the brutality of slavery, to food and the life of the Roman streets, is lovingly laid out around the tale. A student of Rome could learn much from this series, in a similar vein to Philip Matyzak’s 24 Hours in ancient Rome.

But for me, over and above all, the real value of these books is that for the first time, for me, the Year of the Four Emperors has been portrayed in detail, lovingly, from the very ground level up, in a way that unravels it and makes it intelligible. I understood every aspect, for when there was an unexplained motive for some act in that year, Trafford has carefully constructed a plausible narrative that explains it. In addition to this, her characters are fabulously realistic, and she has truly breathed life into some of the historical persons of the year, giving us a life-like portrait. I have long considered Nero a write-off, but I had never pondered on how he must have been seen in light of his successors. Galba was no surprise, but Otho? I had again always written Otho off as a playboy idiot friend of Nero’s who had about as much right and ability to rule as a chocolate orange. Trafford’s Otho has opened my eyes to one of history’s great might-have-beens. The character I take away from her books as my favourite is Otho. And I had similarly written off fat Vitellius, but I had always thought him merely useless, rather than the monster he is here. And as for the slaves and freedmen? Philo is a wonderful narrator. So much so that I’ve asked Trafford if he would be allowed a cameo in my own work. The others are all good, but one character that stands out from beginning to end is Nero’s fake-wife and eunuch catamite Sporus. He absolutely shines in every scene.

So while I peruse my shelves to see what might possibly follow on from that, I leave you with this imperial command: read L. J. Trafford’s books. You will not be disappointed.

The inspiration behind The Haunting of Edenbridge Castle, by Judith Arnopp

To celebrate the release of Hauntings, the collection of historical ghost stories released this month, today I’m hosting one of the other authors in that selection, the talented Judith Arnopp, who’s here to tell you a little about the background of her tale, the Haunting of Edenbridge Castle. I hope you enjoy, and don’t forget to go buy the book. Ten great spooky tales for Halloween, the book link follows at the end of the post. For now, I’ll turn you over to Judith.

It starts with a cold case, an unsolved disappearance of a police officer just before the outbreak of WWII. The story line moves backwards, through the witchcraft trials of the 17th century, and further back to the time of Henry VIII and the childhood of Anne and George Boleyn. And it all takes part in an abandoned castle that rings with the echoes of past inhabitants.

I don’t believe in ghosts but, of course, I’ve never seen one. I expect I’d change my mind if I did. When I was asked to contribute a story to Hauntings, I was in two minds as to how to tackle it. In the end, I just sat down and started typing to see what would happen and Edenbridge was born. A castle teeming with past tragedies, grief and human frailty.

As the astute will have noticed, I originally set the story at Hever Castle, but I changed the name because the history of Hever is so well known, I didn’t want to blur the edges between fact and fiction even further.

I may not be convinced of the existence of ghosts but I have a keen interest in perspective and human perception so the question of how a spirit might view itself was very appealing. Would they know they were dead, or would they just live in a constant spiral of events, reliving their reality, or would they somehow become fused in the life of the person they haunted. Several of the characters in the story question who is the ‘haunt’ and who the ‘haunted.’ To Anne and George, the girl is the spirit but she is certain the people she ‘sees’ are shades of the past. But can she be sure?

The girl sees what others can’t. She knows she is different, even her mother fears her, and they are both all too aware of the events taking place in her own time, the 1640s. Is she perhaps a witch? The girl’s reality takes place during the witch hunts, a reality in which women are persecuted, tortured and hanged. The girl is unsure whether it is worse to be a ghost or a witch and is very much afraid that she may be both.

In the mid-1600s, John Stearne and Matthew Hopkins from Manningtree in the Stour Valley initiated a hatred for witches, which inflated into mass hysteria that spread across the country. Hopkins later rose to fame as The Witchfinder General. Villages around Huntingdon, Keyston, Molesworth and Little Catworth were at the centre and the trials are famous as are the executions. The injustices and horror of those times are horrific, even centuries later.

The knowledge that, They are burning witches at Huntingdon echoes in the girl’s mind. In 1646 nine women and men from the vicinity of Huntingdon were tried for witchcraft; at least four were hanged on Mill Common. The stories spread across East Anglia and beyond and suspicion of witchcraft was infectious. Witchcraft became an explanation for anything vaguely outside the norm and after a farcical trial, the punishment was usually death. Imagine, in that scenario, fearing someone close to you might be tainted; even worse, imagine fearing yourself to be a witch.

Although there are fun elements to my story, it isn’t a jolly tale; ultimately, it is a consideration of the bleak hopelessness of a restless spirit. Anne and Henry’s story becomes more tragic if we imagine them caught in an endless circle of life, with the same unchangeable future forever looming Anybody’s life would be but what could be worse than a young girl, caught amid the thundering echoes of other people’s tragedies, knowing their fate yet powerless to change it. Happy Halloween!

A lifelong history enthusiast and avid reader, Judith holds a BA in English/Creative writing and an MA in Medieval Studies.

She lives on the coast of West Wales where she writes both fiction and non-fiction based in the Medieval and Tudor period. Her main focus is on the perspective of historical women but more recently is writing from the perspective of Henry VIII himself.

Her novels include:

A Matter of Conscience: Henry VIII: the Aragon Years

The Heretic Wind: the life of Mary Tudor, Queen of England

Sisters of Arden: on the Pilgrimage of Grace

The Beaufort Bride: Book one of The Beaufort Chronicle

The Beaufort Woman: Book two of The Beaufort Chronicle

The King’s Mother: Book three of The Beaufort Chronicle

The Winchester Goose: at the Court of Henry VIII

A Song of Sixpence: the story of Elizabeth of York

Intractable Heart: the story of Katheryn Parr

The Kiss of the Concubine: a story of Anne Boleyn

The Song of Heledd

The Forest Dwellers

Peaceweaver

Judith is also a founder member of a re-enactment group called The Fyne Companye of Cambria and makes historical garments both for the group and others. She is not professionally trained but through trial, error and determination has learned how to make authentic looking, if not strictly HA, clothing. You can find her group Tudor Handmaid on Facebook. You can also find her on Twitter and Instagram.

You can catch up with Judith on Facebook here, on twitter here, on her website here, or at her blog here, and most important of all, click on the cover below to head off and buy yourself a copy of the book.

Vikings? In Yorkshire?

Actually, Yorkshire is historically a very Viking area. York (the Roman Eboracum and the Saxon Eoforwic) was the Viking town of Jorvik, and still hosts an annual Viking festival, is home to one of the most high profile Viking museums (the Jorvik Centre) and sits at the heart of an Anglo-Scandinavian land that stretched at times from the north of Scotland to the Thames, occupying the eastern half of the island.

My question, though, was where to find Viking Yorkshire now. I’ve been writing about Vikings for more than a year, and I’ve always considered them somewhat elusive in terms of archaeology. Most of their structures were of wood and earth and other perishables and have left only shadows in the ground to show what they were. They did not leave written records like the Romans, with the exception of things like Runestones and the later, slightly fantastical Icelandic Sagas. Most of what we can now see of the Viking world comes from possessions retrieved from the ground, often from burial sites. So I set myself (and my better half who is an excellent researcher and a keen student of history) the task of looking for what the Vikings have left behind. It is an ongoing project, but if you want to tour the area and find some of the most fascinating survivals, have a look at this:

Clearly York must come first for Viking Yorkshire. The Jorvik Centre remains a groundbreaking museum and surely brings the visitor closer to the Viking world than anything else. In addition to displaying the archaeology of the site and various finds, it houses a magnificent reconstruction of the streets of Jorvik in those days, right down to the noises and smells (beware of them!) At the other end of the city from the centre, you will find the Yorkshire Museum, home to the city’s (and the county’s) history and archaeology from the earliest days through to modern times, including tantalising glimpses of the Viking world. Look out in particular for the Cawood Sword, a late 11th century Viking-style blade. Near the museum, in the gardens, is a section of the city walls that shows the stages of their construction as layers, and it is fascinating to stand there and picture the ground level during the Viking era (around the level marked as ‘Anglian’.)

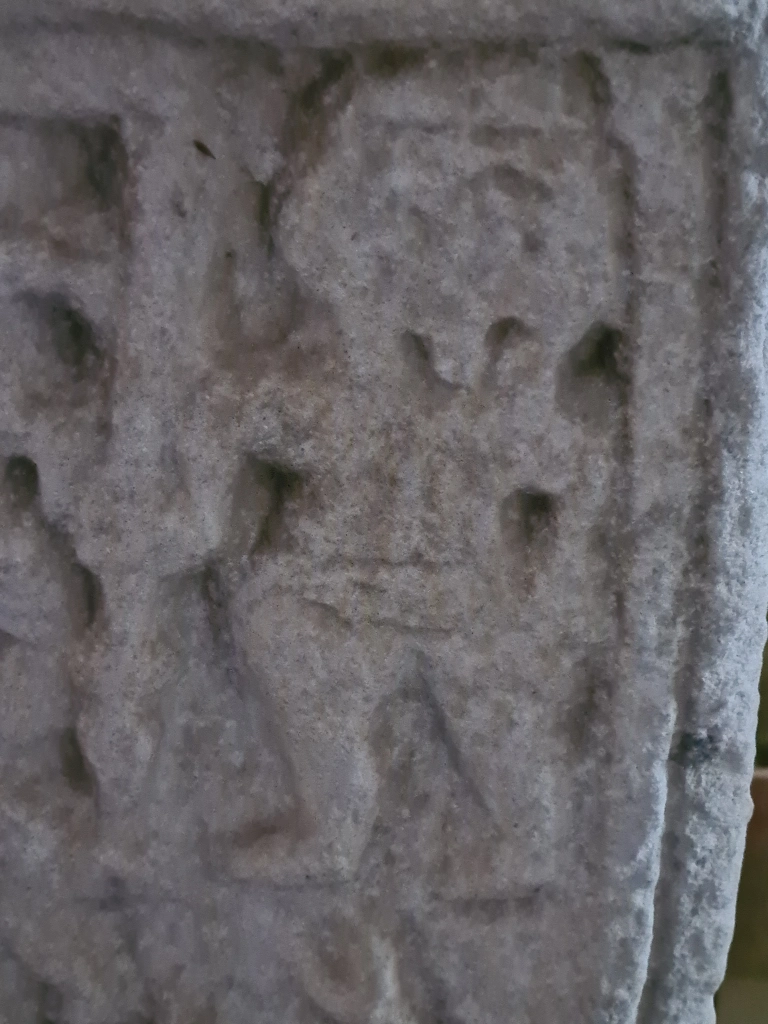

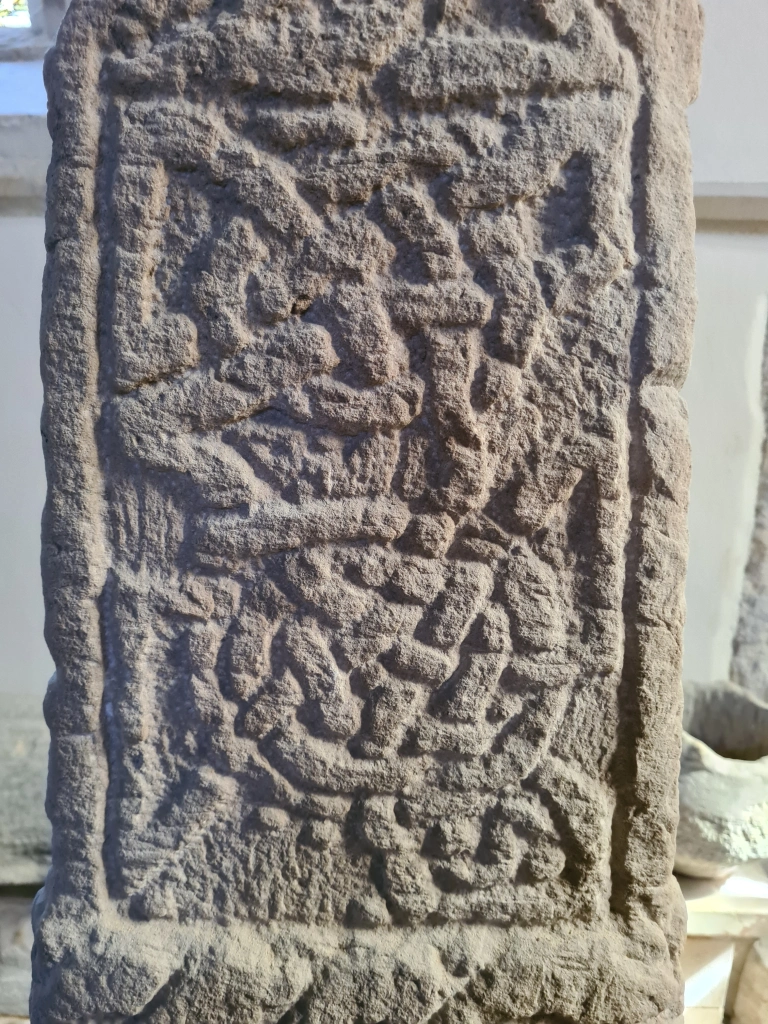

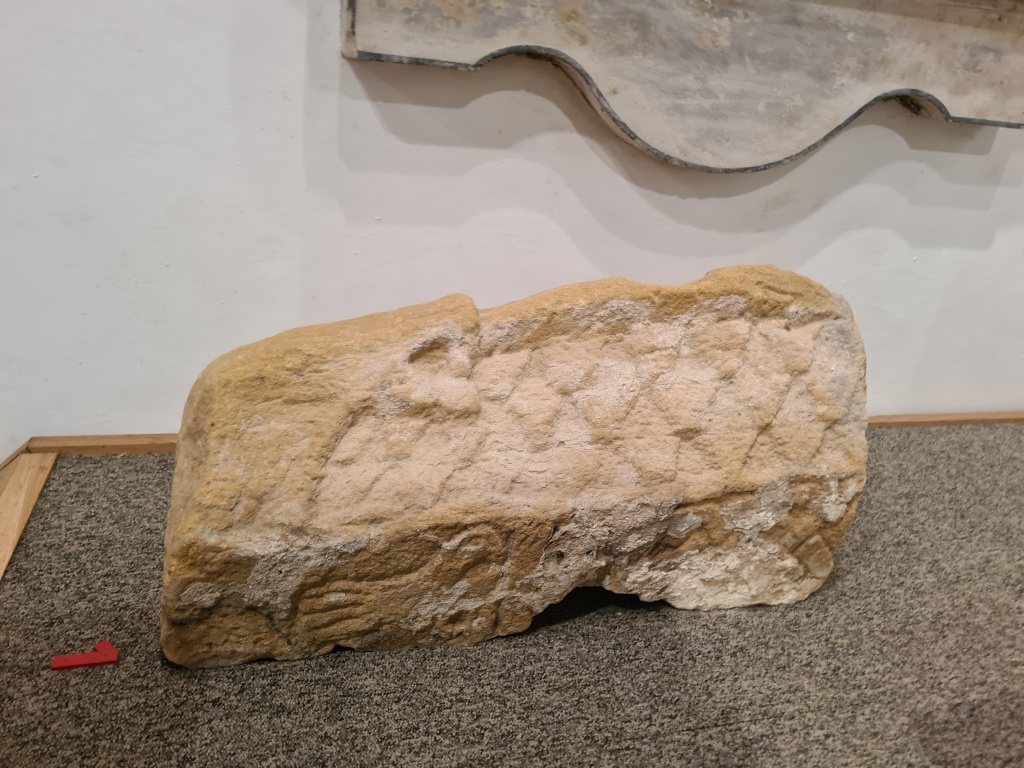

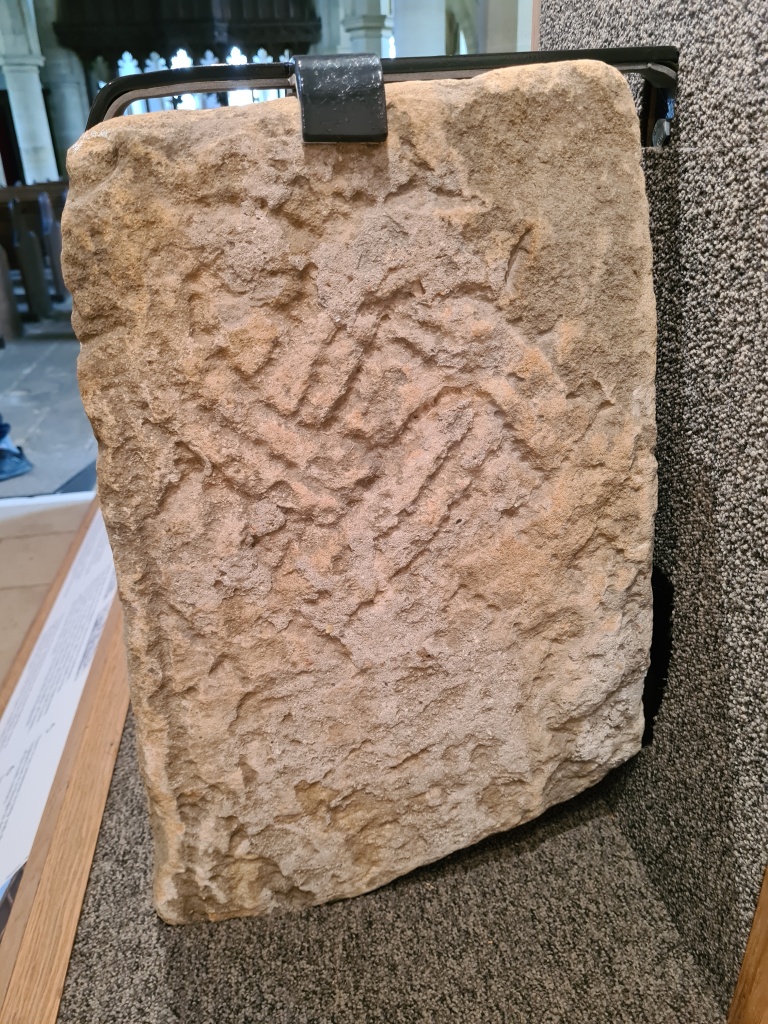

Outside York, too, there are amazing places to visit. We have recently toured a variety of churches, looking at Viking sculpture and grave markers (often the so-called Hogsback stones). And while one might think to look in the great cathedrals and museums for such things, you might be surprised where else you can find them. Here, then, is a C-shaped Roman tour of the North Yorkshire Moors. Let’s begin with Saint Andrew’s Church in Middleton, near Pickering. The church itself is fascinating, with a pre-Conquest Saxon Tower, but inside are a collection of wonderful 10th century Viking crosses, displaying wonderful images, from armoured warriors to Jellinge-style animals.

Not far from Middleton, one can find the church of Lastingham, an oddly Romanesque looking building, given its location. Lastingham was once a priory, and while the church itself is old and fascinating, the true treasure here lies in its crypt. The crypt of Lastingham is itself 11th century, but is built upon the site of monasteries going back to the 7th century, deep in the Viking era. It is a stunning structure, containing fascinating stones from the Viking age, including a Hogsback. While visiting, it would be a criminal oversight not to stop for a drink and a bite to eat at the Blacksmith’s Arms across the road.

On my grand loop of the Yorkshire Moors, we now come down from the Scarborough road, via Sutton Bank, one of the greatest views in the country, and head north in the Vale of York to Northallerton. Just outside this market town, to the north, the village of Brompton has become more or less a suburb. Its church is unassuming and often overlooked. I personally had overlooked it often, to my peril. Brompton church, along with Durham cathedral, has the best preserved and most stunning collection of Viking hogsback stones to be found in the country. Indeed, the two places of worship split the collection between them. The quality of the carving on the stones in Brompton defies once and for all any notion that the Vikings were not an artistic people. The work is exquisite.

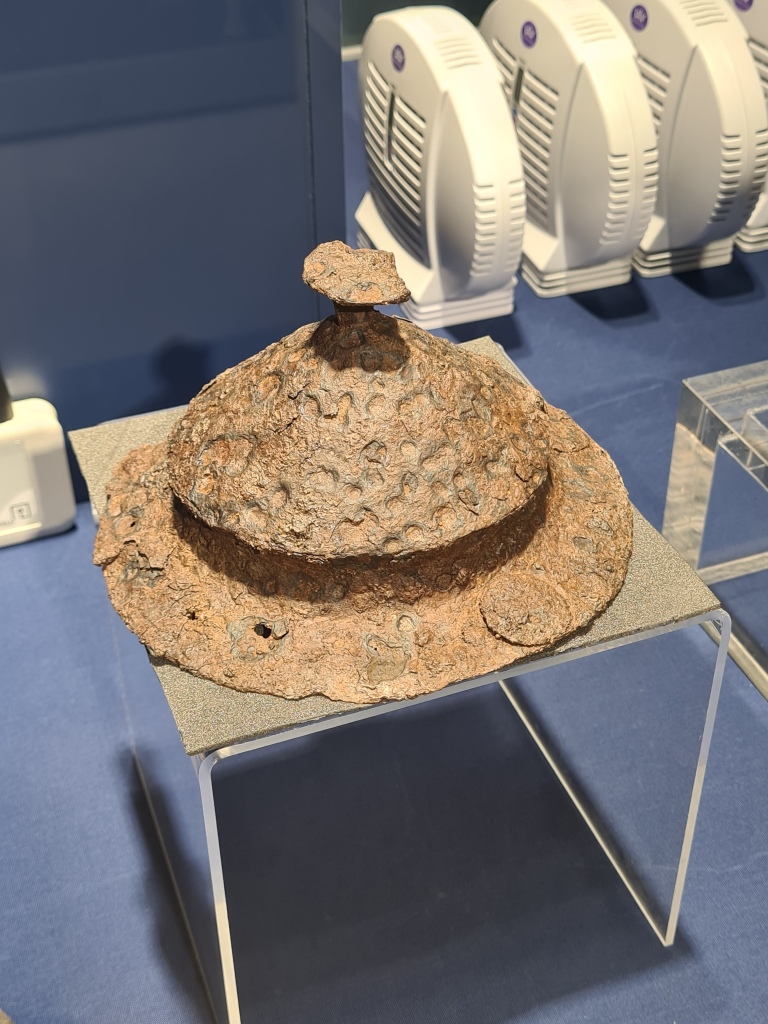

Moving north once more, we’re going to take a step away from the stones for a moment. Just to the south of Stockton on Tees, drop in to the Preston Park Museum. In fact, the museum was unknown to me before this year, but now I am stunned by what I have missed. Quite apart from the almost Beamish (been there?) reconstructed Victorian street and the many other eras’ exhibits, a few Viking stones of a lesser quality than those you’ve already seen are of interest, but above all, among a few Viking finds, Preston Park holds a gem, so to speak. The first Viking helmet found in Britain, hauled out of the Tees near Yarm in the 1950s. Not only that, but this 10th century helmet is only the second near-complete Viking helmet found in the WORLD! Get thee to a Preston Parkery…

Before we take in our last Viking exhibit this trip, it is worth a side visit to Kirkleatham Hall near Redcar. Along with the many other exhibits there are the remains of the tomb of a so-called ‘Saxon Princess’, taken from a ‘bed-burial’ nearby. The jewellery on display there is magnificent, and in temporal terms the distance between this princess and our Vikings is only a short hop. Take the time to visit this wonderful little museum and see this display. The Saxon Princess deserves far more fame than she seems to have, given that we found her entirely by accident.

To end our tour, having driven a great C around the North Yorkshire Moors, head for the small village of Sandsend, just north of Whitby. Before you reach Sandsend, you will go through the village of Lythe and find the church of Saint Oswald. Saint Oswald was extensively repaired and rebuilt during the last century, and during those works, some of Yorkshire’s best Viking stones were discovered built into the walls. These stones are now on display in the church, including a magnificent image of Odin being devoured by wolves, amid Viking crosses, a clear view of that strange half-world when the Vikings had been Christianised, but the legends of their people clung on in hearts and minds, even in Christian churchyards.

So that ends a tour of Viking Yorkshire. Stay tuned, and I’ll take you on another tour soon. In the meantime, may Odin have your back, and I hope you enjoy Wolves of Odin: Blood Feud. Happy reading.

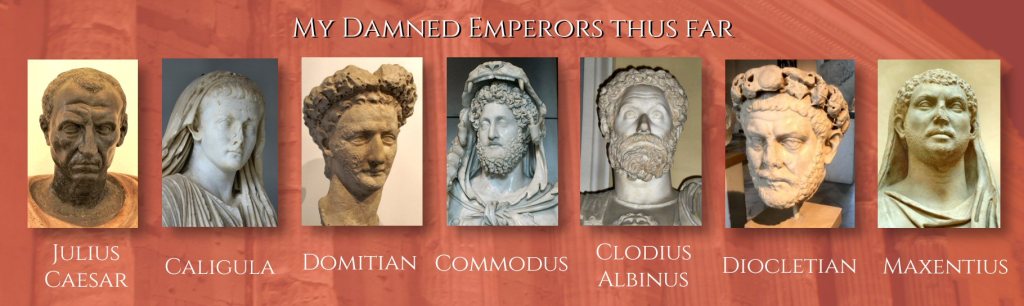

Damned if you do, Damned if you don’t

(or Why I choose to write about the ‘damned’ emperors.)

Alright, you’re going to argue with me from square one, but in my opinion, if we can call Augustus an emperor, when he never acknowledged himself as one and assiduously kept republican characteristics, then we might as well apply the same to the somewhat infamously dictatorial Caesar, his great uncle.

I trust we need not delve too much into the history of this man. His life and death are fairly well known by even the least academically minded. Et tu, brute. Infamy, infamy… they’ve all got it infamy! And so on. So, yes, Caesar was not an official emperor, yet he bears all the hallmarks of it. By his death he held unshakable power in Rome, and the laws had been repeatedly bent or ignored entirely to allow him to continue his rule. It was rumoured that had he lived, he intended to move his centre of power away from Rome to Egypt, which was likely one of the contributing factors to his assassination.

Though Caesar never suffered the specific Damnatio Memoriae that later emperors enjoyed, his death was no murder by a power-hungry opponent or a personal beef settled with a blade. Caesar was stabbed 23 times, and each blade was wielded by the great and the good of Rome. After his death, Brutus addressed the crowd with the words ‘We are once again free.’ If this is not being damned by the senate of Rome, then I don’t know what is, so we’ll proceed with that justification and classify him as damned.

And it’s important that I do, because that’s where it all began. I came to write about Caesar through the eyes of one of his officers in the Marius’ Mules series, the first novel I ever wrote, back in 2003. Up to that point, I had viewed Caesar as a bold and heroic character. A genius and a general supreme. Essentially, history’s common view. And unlike most of my forays into the world of such characters since then, where I have had to look beyond later character assassination to redeem a human within, in Caesar’s case it is more a matter of finding fault with a man given to us as a perfect Roman, because the sources we have for Caesar generally praise him. Once the civil war that followed his death had settled, it was his own blood who controlled Rome for the next century, and the entire imperial system owed itself to Caesar and his direct successors, so while emperors may later have reviled some of their predecessors, Caesar remained on his pedestal throughout. As such, accounts of him were guaranteed to be positive. Perhaps most of all, the account we have of the high point of his career was written by the general himself. There may, therefore, have been something of a bias involved.

As such I spent my time throughout the series glimpsing tantalising images of a less perfect man, and tried to portray him as such. Caesar loses his temper a few times, yes, but he is always gracious and merciful, brave and powerful, shrewd and resourceful in his writings. Surprise, eh? But the first works to cover his campaigns that were not written by him were the “Alexandrian War” and the following “African War”, both of which were probably written by his deputy Aulus Hirtius. In those two works, Caesar’s actions often come across as rash, hasty and ill-thought out. In both cases he still wins the day, but unlike the earlier texts of Caesar himself, they portray a man who essentially ****s up the entire campaign and only survives through a combination of thinking outside the box and blind luck. Add to this the fact that Caesar had many lovers, possibly several love-children, and three wives, the last of whom was still his wife when he was messing around with Cleopatra, and the image that begins to form is of a rather less than perfect man for all his genius and glory.

This is why I loved to write about Caesar, and this is what has spurred my interest in other such cases. The sheer fascination of delving into a well-recorded character and trying to reassemble a real person from the caricatures of history.

Next up is Caligula. This was my first foray into truly studying a damned emperor. Most people will be aware of Caligula, at least as a raving lunatic, a murderer and a weird porn character played by Malcolm McDowell. There probably has not been an emperor damned after his death who became as famous as this man. He is given to us as the man who made his horse a consul, who fought a war against the sea god, who made his men gather shells and stones and bring them back to Rome as spoils of war, of an incestuous weirdo who slept with his sisters.

Alright, so that is what we’re told. Caligula ruled for four years and upon his assassination, he was the first emperor to suffer what we now call Damnatio Memoriae, in which his name was erased from everywhere, his statues smashed, his laws repealed, his coins defaced, his very name condemned, and he being denied the right to ascend to godhood. He was stabbed by members of his own Praetorian guard, who suspiciously found Claudius hiding nearby and proclaimed him emperor immediately. It might be noted that Claudius was Caligula’s uncle, who was undoubtedly rather put out for those four years that the imperial throne had completely bypassed him. He was not treated well by Caligula, and so a suspicious man might suggest that Claudius was behind the plot to murder his nephew. Otherwise it’s all a little too convenient.

And the odd thing, if we accept these stories at face value, is that Caligula seems to have been very popular with the majority of Rome. The army liked him. The masses liked him. The only people that didn’t like him were the senatorial crowd, who, you might note, were the ones who wrote all the stories of his madness after his death. Now, a suspicious man might be scratching his chin and wondering how much of what we know is actually complete garbage, and what the real Caligula (who’s true name, coincidentally, was Gaius Julius Caesar) was actually like.

Just to give a couple of examples of my research and conclusions on the real Caligula, we’ll first take his horse, Incitatus. There is no denying Caligula loved horses and the races and so, in fact, did many emperors. But what do we actually know of Incitatus? The horse is recorded in two sources. Suetonius tells us “Besides a stall of marble, a manger of ivory, purple blankets and a collar of precious stones, he even gave this horse a house, a troop of slaves and furniture, for the more elegant entertainment of the guests invited in his name; and it is also said that he planned to make him consul.” Very well, he spoiled the animal for sure, if Suetonius can be trusted. But even Suetonius, who repeatedly condemns Caligula only gives us a vague rumour that he would have made his horse a consul. Cassius Dio gives us “One of the horses, which he named Incitatus, he used to invite to dinner, where he would offer him golden barley and drink his health in wine from golden goblets; he swore by the animal’s life and fortune and even promised to appoint him consul, a promise that he would certainly have carried out if he had lived longer.” More of the same, and this time only personal opinion that he would have done such a thing. One might remember that Suetonius was writing imperial biographies in the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian, some 80 years after Caligula’s death. His source material was already biased, for Suetonius was not born until 30 years after Caligula’s death. Similarly, we might view Dio with suspicion, for he was even later, writing nearly two centuries after Caligula’s death and basing his tale on a long-held tradition of madness. Thus, our main sources are the equivalent of me now putting together a biography of a Hanoverian monarch, only with much less to work from. Both of those writers were working with an imperial agenda in mind that necessitated the condemning of Caligula and the Julio-Claudians, and if these recorded events ever actually happened, a tempting suggestion is that the whole thing was a rather acidic joke on Caligula’s part aimed at humiliating the senators.

Similarly, the story of the chests of shells and pebbles the legions carried back as plunder can be seen very differently, when one realises that Caligula had gathered his legions for an invasion of Britain, where they seem to have revolted against him on the French coast. What better humiliating punishment for soldiers who have rebelled than making them carry chests of stones all the way back to Rome as the spoils of their war? Again, this reeks of Caligula’s very dry and potentially dangerous sense of humour. Not a sign of madness, but an indication of a man not afraid of dark humour aimed at those who defied him.

Essentially, when one looks deeper at Caligula, one can see a character greatly different from the one presented to us. Oh, he was no god, for sure. His sense of humour seems to have been cruel and acerbic and to have missed the mark repeatedly. He was suspicious (but then any man who had watched his entire family arrested and executed in his youth might be suspicious). But he also appears to have been glorious, beloved of his people, brave and wily. One thing he does not seem to be, if you pull apart the sources, is insane. This, then, is what I love about damned emperors.

Next up is Domitian. The second son of the renowned Vespasian and brother of glorious Titus, Domitian never expected, and was never expected, to rule. He was . History has presented us with a quiet and bookish, yet also wicked and brutal, character. Domitian ruled for a good 15 years, in the end falling to a conspiracy of the emperor’s own freedmen. His character has come down to us mainly through the writings of Tacitus and Suetonius, both of whom solidly condemn him, and yet one might note, both of whom are writing in the reigns of the emperors who only owed their existence to the fall of Domitian and the Flavian dynasty, and who naturally vilified their predecessor in order to justify their own power.

If, however, one looks at the scant evidence we have of contemporaries who were writing during the time of Domitian, such as Statius, we find the emperor being praised and portrayed as a glorious figure. One must always be aware of bias in both directions with ancient biographies.

I have yet to write a novel centring on Domitian, though it is already planned and very much in my sights. However, in my first foray into non-fiction, I have biographised the general Gnaeus Julius Agricola, the father-in-law of Tacitus, and a man who served during Domitian’s reign. In researching this, I repeatedly came up against Tacitus assassinating the emperor’s character largely in order to heighten the glory of his subject. But often in Tacitus, while he attributes to Domitian a truly abhorrent character, when he actually provides detail, it often doesn’t marry up with that image.

As examples, Tacitus tells us Domitian: “was by nature a man who plunged into violence“, of his “sinister intentions“, of “the emperor’s cruelty“. He tells us straight that Domitian resented Agricola’s success and popularity, and harboured a great hatred. And then in his text, he tells us also that for Agricola “Triumphal decorations, a public statue, and all the insignia that go with an honorary triumph were therefore decreed by the senate on the emperor’s command, coupled with a flattering speech.” For an emperor who had no trouble imposing imperial will, this seems rather at odds, as does the fact that when jealous opponents repeatedly accuse Agricola of crimes, the emperor throws out the cases. Most impressive of all, when Agricola fell ill in his last days, Tacitus tells us that Domitian sent court physicians and freedmen to attend him, and even that there were “more visits […] than is usual with emperors.” Though Tacitus tries to inflect all these events with sinister motives, it really does not add up, and what we are left with is the impression of an emperor who actually values and cares for his general.

I can’t wait to get my teeth into a full novel about this fascinating man who was so damned and despised after his death and yet who had been a secret agent, an overlooked second son, and who had inherited an empty treasury and left a wealthy Rome for his successors and a huge architectural legacy across Rome.

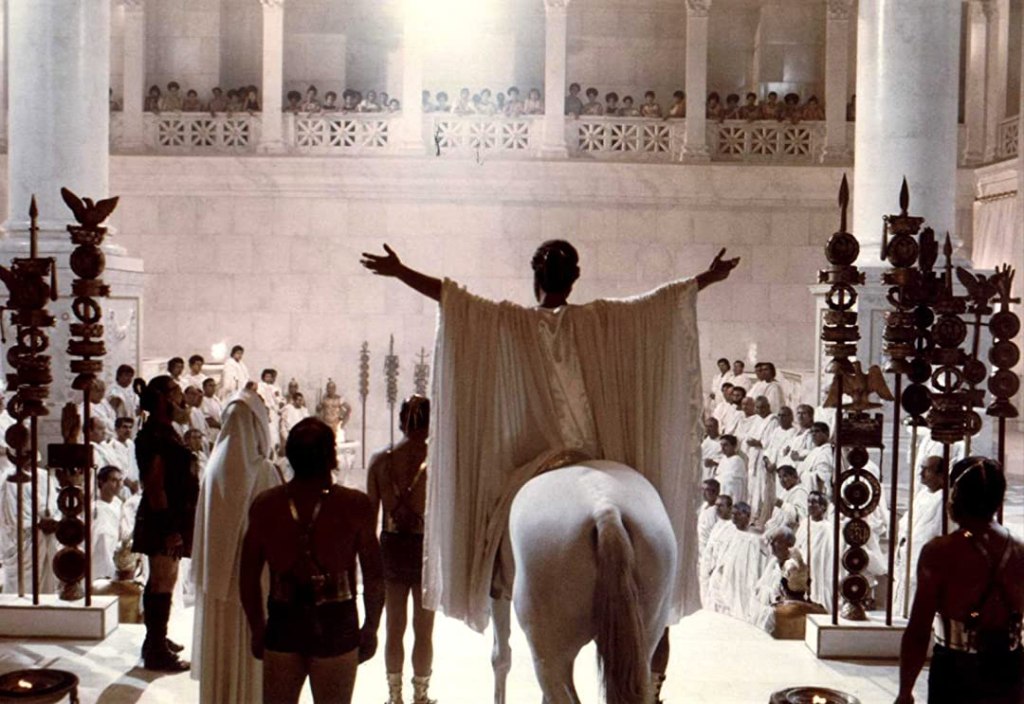

Ok, you may not have recognised him from the name, but I bet the pic jogs a few memories. Commodus, portrayed above by Joaquin Phoenix in the movie Gladiator, was my second foray into fictional biographies, with an eponymous novel. Commodus was my attempt to delve into the sources and tear apart the chaff to find the real character, as I’d done with Caligula.

Commodus is given to us mainly by Cassius Dio, Herodian and the Historia Augusta. While not portrayed as an insane and dangerous lunatic as was Caligula, he comes across as a megalomaniac and a man given to wild notions and flights of fancy, often cruelly at the expense of others. Once again, though, we must beware of the sources. We can say with some certainty that Commodus came to blows with the senate more than once, and that there was a gulf between the two that was filled with resentment and distrust. As such, one might expect senators to be somewhat damning of the emperor who had so defied and belittled them. Cassius Dio was one of those very senators Commodus hated. Herodian’s career is not fully known, but there is solid circumstantial evidence that he too was a senator at that time. The Historia Augusta’s section on Commodus is likely based on the works of Marius Maximus who, you guessed it, was of senatorial rank during the reign of Commodus. Thus our three main sources were all naturally hostile towards the emperor. Can we trust what we’re told? In this case less even than in other such works.

In some places, these biographies clearly delve into the fantastical and ridiculous. The HA gives us the laughable event: “he put a starling on the head of one man who, as he noticed, had a few white hairs, resembling worms, among the black, and caused his head to fester through the continual pecking of the bird’s beak — the bird, of course, imagining that it was pursuing worms.” Dio tells us of Commodus in the amphitheatre that “On the first day he killed a hundred bears all by himself“. Herodian, at least, steers largely clear of such fanciful notions, but even he dips occasionally into hyperbole.

Of the accusations of megalomania, several of his acts are cited, and yet once again, a lot of this is down to the angle one takes on them. He is known (confirmed in inscriptions) to have changed the names of the months to his own twelve names: Lucius, Aelius, Aurelius, Commodus, Augustus, Herculeus, Romanus, Exsuperatorius, Amazonius, Invictus, Felix, Pius. Mad? Really? When the month of Quintilis had been renamed after Julius Caesar two centuries earlier, and shortly after that, Sextilis had been renamed for Augustus – July and August as they now are? One might suggest this is a little over the top, yes, but there was a solid precedent for it, and that its usage is recorded even out in the Syrian desert suggests that it was not really considered unacceptable by provincials. And how crazed was it that he refounded Rome after a disastrous fire and named the restored metropolis Colonia Lucia Annia Commodiana after himself? Mad, right? So why do we honour and celebrate Constantine for refounding Byzantium as Constantinopolis? Is that not the very same megalomania at work? Or perhaps we should worry about his identification with Hercules, for he dressed as the god at public events. Surely that’s properly barking mad? And yet a bust of a young Commodus portrayed as Hercules as a boy can only have been commissioned by his father, the great Marcus Aurelius, and so was Commodus perhaps merely continuing his father’s vision? Moreover, the identification of emperors with that god arose once more a century later during the tetrarchy, so really this is not an isolated thing, but an imperial trend.

In my research I came to the conclusion that Commodus was neither wicked nor insane, but rather suffered Bipolar disorder (previously known as Manic depression), which would fit his darker moods and periodic withdrawal from public life, as well as his somewhat over the top glorious notions. Certainly, Commodus cannot be the monster we are given.

Following the death of Commodus and the brief reigns of two successors, the next real power in Rome was Septimius Severus, but to secure his throne, he had to put down usurpations by Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus. Niger never managed to secure acceptance by the senate, and so was not truly an emperor, though Albinus was briefly legitimised by Severus.

I have yet to delve in depth into the lives of these two usurpers, though both have appeared in the Praetorian series, particularly Niger, in which they are portrayed simply as ambitious Roman noblemen. Let’s largely skip them for now and move onto more fertile ground.

For our last exploration, I’ve put the final two on my list together. Diocletian was the man who founded the tetrarchic system (splitting the empire in half and appointing a senior and junior emperor to each.) He ruled from 284 to 305 AD. Maxentius, one of several claimants to the western empire as the system collapsed again, reigned from 306 to 312. Both men are among the last to be damned, and their reputations have suffered in particular because of their opposition to Constantine. Their biographies come to us mostly through Christian writers who favoured their hero Constantine, and so any man Saint Constantine was set against is naturally vilified.

Of Diocletian, Eutropius says “He used his victory, indeed, cruelly, and distressed all Egypt with severe proscriptions and massacres. Yet at the same time he made many judicious arrangements and regulations, which continue to our own days,” gracing us with an unusually rounded image of a man both damnable and laudable in different ways. Cruel and dangerous, yet clever and an able administrator. Indeed, this juxtaposition is echoed throughout Eutropius: “He was willing to gratify his own disposition to cruelty in such a way as to throw the odium upon others; he was however a very active and able prince.”

Lactantius, on the other hand, not only gives us a very one-dimensional view of the emperor, but he also makes his bias very plain from the outset: “While Diocletian, that author of ill, and deviser of misery, was ruining all things, he could not withhold his insults, not even against God.” Thus, it is with extreme care that we have to consider anything Lactantius tells us. Diocletian was one of the greatest persecuters of Christians in history, and so the views of Christian writers are unlikely to be positive.

Actually, the evidence for Diocletian’s damnation is scant, for he retired and died naturally in a villa in Croatia, though an inscription found in Rome in which Diocletian’s name has been scratched out and replaced with that of Constantine hints that Diocletian’s reputation went the same way as his co-emperor Maximian, damned by Constantine even if he later rehabilitated the man’s memory. Diocletian is something of a bit part player in the Rise of Emperors series that I co-wrote with Gordon Doherty, an Emperor Palpatine to Galerius’s Darth Vader. In our work he is characterised as cruel and dangerous, possibly even mad. This may be a caricature, but given that even the more positive biographies of the man make him cruel, it seemed natural to follow the trend. Quite simply, even if you’re not a Christian, given that Diocletian presided over one of the most brutal and widespread persecutions in history, it is hard to see him as little more than a villain.

To the last of our emperors, then. Maxentius is the son of that very same Maximian mentioned above. Maxentius is my protagonist throughout the Rise of Emperors series, alongside Gordon’s Constantine, and with him I had to apply much the same system of research as with Caligula and Commodus. Maxentius has once again come down to us as the villain of the piece, a brutal and cruel usurper facing the sainted and wonderful Constantine. Our sources for Maxentius are universally Christian and therefore in Constantine’s pocket, and so it should come as no surprise that they damn Maxentius. The approach here, though, is different to those earlier emperors, for there is no accusation of madness among these biographies. Maxentius is simply wicked, dangerous, licentious and evil.

One might note from the outset that Maxentius had every bit the same claim to the Western Empire as Constantine. Both had been sons of emperors, and both had expected to be included in the succession. When they were not, both took matters into their own hands, Constantine proclaimed by his army in York, Maxentius proclaimed by the Praetorian Guard and the senate in Rome. There are, in fact, few lines in the sources at all on Maxentius. He is not well covered by contemporary writers.

Lactantius, one of Constantine’s great biographers, only deals peripherally with Maxentius, though he labels him from the outset “a man of bad and mischievous dispositions, […] proud and stubborn.” Though he treats the events of Maxentius’s reign only in snippets, even at the end, the demise of Maxentius is noted as “The hand of the Lord prevailed.” Thus is Maxentius presented to us as an agent of the devil, despite the fact that there is no real evidence of Maxentius’s cruelty towards Christians. Indeed, there is only actually one direct story of the man persecuting Christians.

The somewhat fanciful legend of Saint Catherine of Alexandria says that she went to Maxentius when he instituted persecutions. She argued her stance and managed to out argue 50 pagan philosophers summoned by the emperor. At this point he loses his temper and begins to imprison and torture he, eventually leading to her death, when her body oozed something like milk instead of blood. Quite apart from there being no evidence of a Maxentian persecution, the story holds less water than a cotton colander. And just to hammer a nail into that coffin, the Christians of Rome had been forbidden to elect a high priest (a pope) under Maximian, yet Maxentius saw the investiture of three popes. Hardly the actions of a persecutor of Christians.

Beyond Lactantius, various Panegyrics do Maxentius little service, though one of the other main sources is the 5th century historian Zosimus. Zosimus periodically has a stab at Max’s reputation here and there with phrases like “conducted himself with cruelty and licentiousness” and yet his treatment of the actual events is surprisingly neutral, and even tips in the direction of admiration occasionally with moments like “They would have destroyed the whole city, had not Maxentius soon appeased their rage.”

The simple fact is that whether the sources are entirely damning or just a little dubious, Maxentius is given to us as a hater of Christians, a bane to Rome and a dangerous and unacceptable usurper. No one has a good word to say about him, and yet we have to remember that all those writing do so under the aegis of his enemy and successor, Constantine. So if Maxentius the hater of Christians, the tyrant and the despot is a fiction of vilifying biographers, what do we know of Maxentius the real man?

Actually, the most telling thing about Maxentius comes from surviving archaeology and geography. While Galerius, Constantine, Licinius, Daia, and every other weasel barking during the tetrarchy, sought imperial power, each and every one imagined the seat of that power somewhere in the provinces. Serbia, Turkey, Bulgaria, Germany, each emperor ruled from a court somewhere in their heartland. Maxentius was something different. Though he had been born into a once humble family from the Balkans, it was Rome for which he stood and which became the heart of his domain. The only Roman imperial sceptres and regalia ever found have been attributed to him. At the very end, when facing Constantine, he consulted Rome’s most ancient scriptures and fought to protect Rome, even turning its walls into the impressive specimens we can see today. Logic and a little investigation suggest that despite his provincial origins, Maxentius was the only claimant of the era who represented Rome.

Furthermore, Rome had seen only a few eras of great public building in 300 years of emperors, and these projects were all attributed to great men. Augustus remodelled the forum and began to fill the Campus Martius with monuments. Vespasian and Titus extinguished the excesses of Nero and replaced them with magnificent public buildings. Trajan filled Rome with great works for the people. Other rulers constructed buildings in scattered numbers, but only the greatest of emperors embarked on city-changing projects of grand public works. And the last one to do so? The last emperor to embark on a plan of public buildings in Rome was Maxentius. And were the works mere self-aggrandizement? Alright he may have built a villa with the mausoleum of his son on the Via Appia and a new private bath on the Palatine. But he also built or reconstructed all of this:

If one looks at the archaeology and tries to ignore the worst of the propaganda, what comes out of it is the image of a traditionalist. In a world where emperors are trying to change the administration, the geography, the capital, even the religion of the empire, Maxentius stands for Rome, as an echo of the great emperors of the past. In a way, he is the last great pagan emperor of Rome. Indeed, he is the last emperor to rule from Rome, and the last emperor to reside on the Palatine. Maxentius is, to me, the last true Roman emperor.

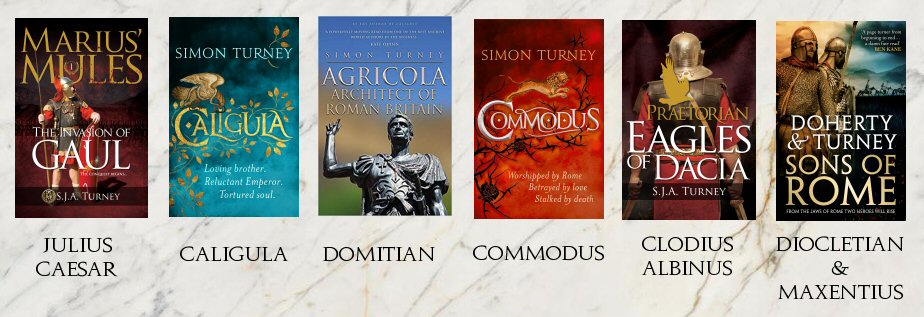

So that’s it for now. I shall in time investigate and rehabilitate others, and certain names are already in my sights, but if you want to read about the emperors so far, here are the books. All are available through online stores such as Amazon and the iStore (except Agricola which is available as a pre-order only), and Caligula, Commodus and Sons of Rome are available in your local bookstore also. Happy reading and let’s reform the reputations of a few great men…

Rise of Emperors

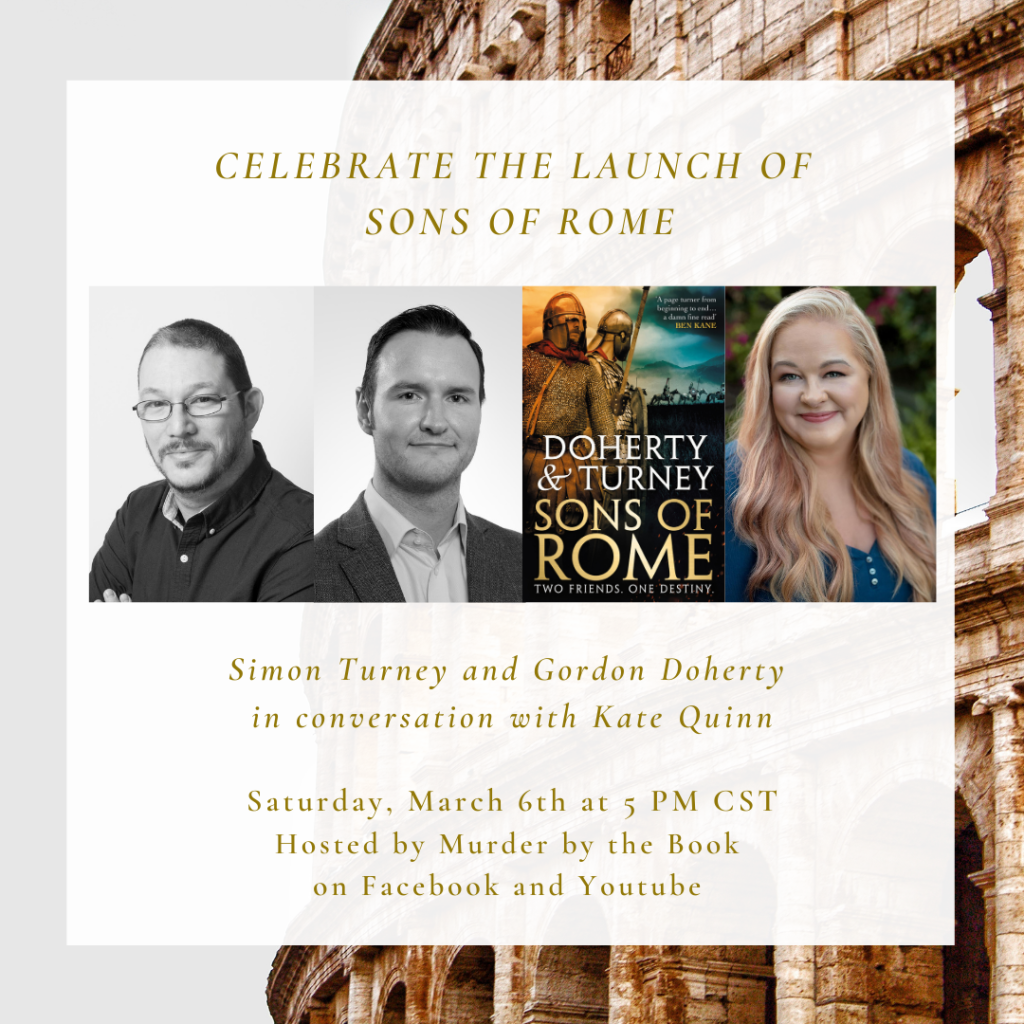

The Rise of Emperors series charts the childhood, the rise, the rift, the struggle and the war between the later Roman emperors Constantine and Maxentius at the end of the 3rd/beginning of the 4th century. Many of you will already have read book one, but here is a run-down for anyone interested in our take on the end of the Tetrarchy.

The first book, Sons of Rome, is now out in digital and hardback formats in the UK and the USA (the paperback is released on 1st April in the UK). Sons of Rome follows the childhood and the friendship of the two emperors, from the time when they are but the children of powerful men, through to the fall of the Tetrarchy and the seizure of power by both men, each claiming the same empire as their own. Buy the book here.